RED Color History and Values. Article by Guillaumette Duplaix, Editor of RUNWAY MAGAZINE, Keeper of Colorful Truths. Photos: RUNWAY MAGAZINE archives.

History & Values

RED COLOR

#ff0000 – RGB 255 0 0 – H 0° S 100% L 100%

Red is one of the three primary colors and the most prominent on the chromatic circle, nestled between orange and purple.

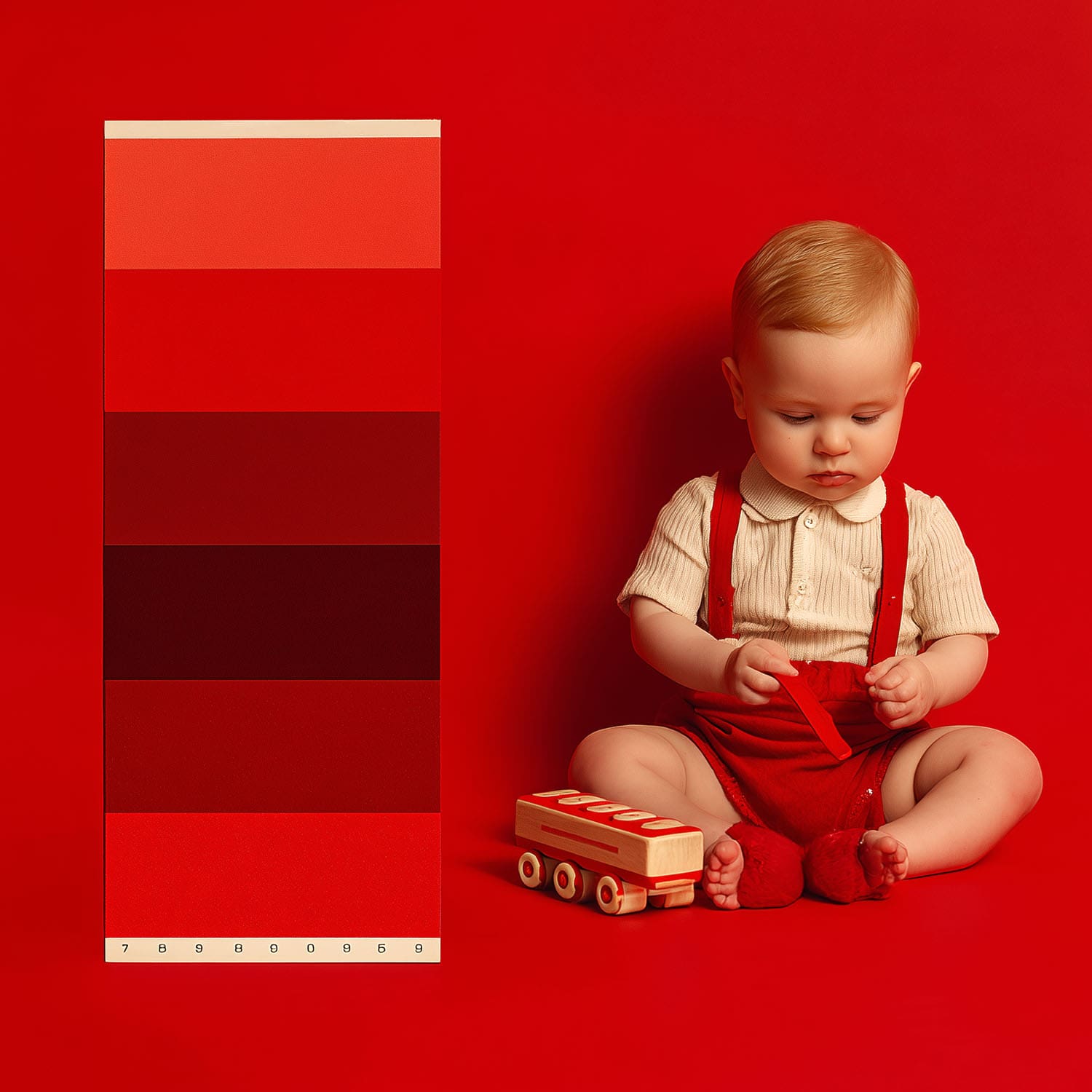

The Perception of Red

Red is the first color young children are able to identify. As early as 12 weeks of age, infants begin to display preferences for certain hues—red being among the first perceived and recognized. The way children between 3 and 5 years old respond to colors is a key developmental indicator.

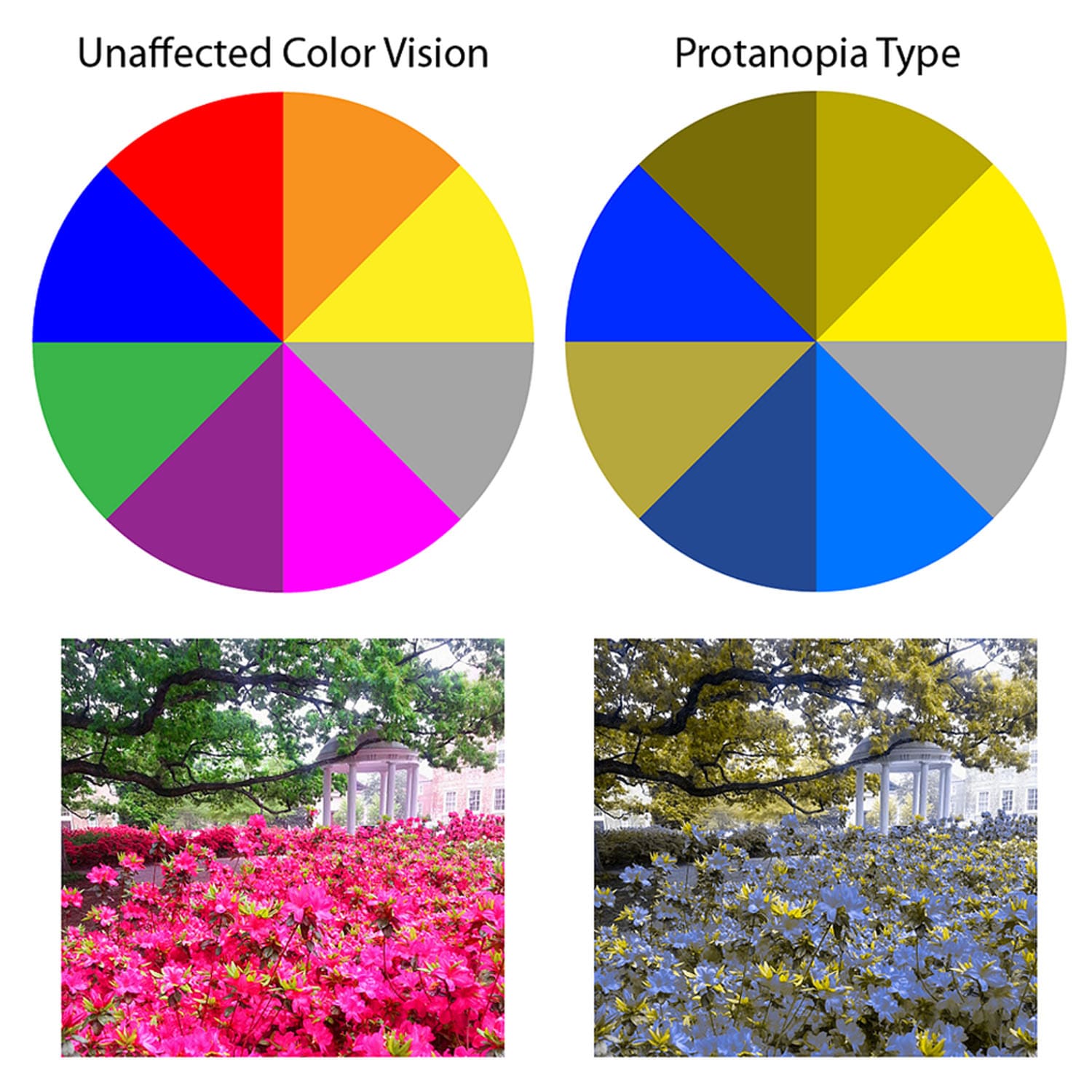

Did you know that 8% of people can’t perceive red at all? This condition is called protanopia, a hereditary form of color blindness in which the red-detecting cones are absent. Individuals with protanopia see red tones as shades of green or grey and rely only on blue and green to perceive the world. What appears as a rich tapestry of reds, oranges, yellows, and greens to the average trichromatic eye becomes a far more limited spectrum.

The human eye perceives red when it detects light with wavelengths between 625 and 740 nanometers—a range just before the invisible realm of infrared, which we feel as heat but cannot see. In optical terms, red is produced when the retina’s L-cones (sensitive to long wavelengths) are stimulated more than the S- and M-cones. Interestingly, women tend to distinguish red hues more easily and broadly than men.

While primates can perceive the full visible spectrum, many mammals such as dogs or cattle have dichromatic vision, meaning they can only see blues and yellows. Red and green appear as shades of grey—hence the myth of the bull charging at a red cape is purely about movement, not color.

The History of Red

Prehistoric Times

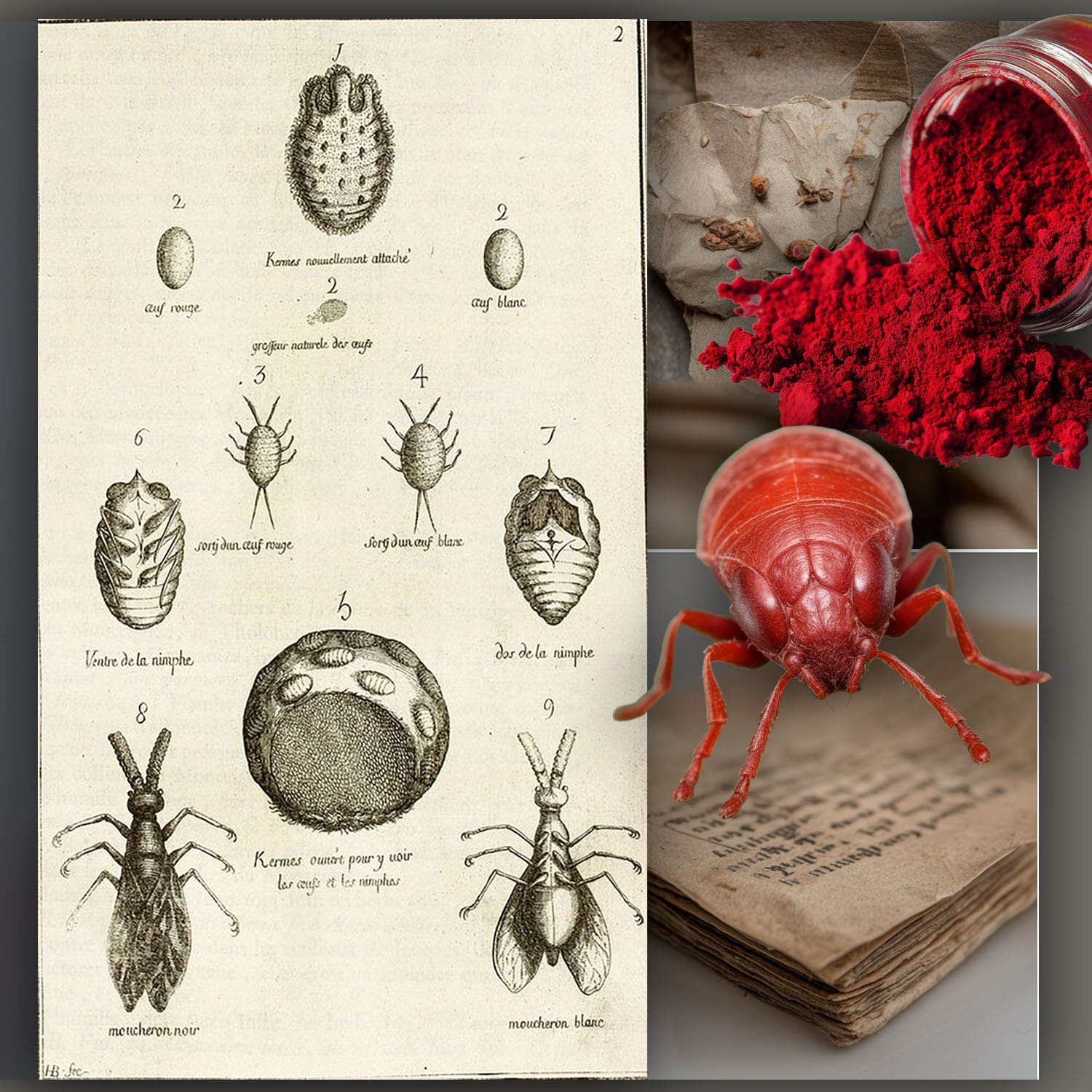

Red, along with black and white, was one of the first colors used by Paleolithic artists, largely due to the availability of natural pigments like red ochre and iron oxide. The madder plant, whose roots produced a deep crimson dye, was used extensively across Europe, Africa, and Asia.

Another ancient red dye, kermes, was made by drying and crushing the bodies of female insects from the Kermes genus—specifically Kermes vermilio. This dye was already in use during the Neolithic era.

Ancient Civilizations

In Ancient Egypt, red symbolized life, vitality, and triumph. Egyptians adorned their skin with red ochre during celebrations. Women used it as cosmetics for their cheeks and lips, and henna was employed to dye hair and paint nails.

In Rome, red signified festivity and military prowess. Brides wore red veils called flammeum, and gladiators’ skin was painted red. Roman generals receiving a triumph had their bodies painted entirely in red in homage to Mars, the god of war. Roman soldiers wore red tunics, and the Roman military standard bore a red background with the golden initials SPQR.

Among the Maya, red had both sacred and hazardous implications. They used cochineal insects for red pigment and cinnabar, a mercury-based mineral, for a brilliant but highly toxic vermilion pigment. The toxicity of cinnabar left a lasting ecological impact on the soils around ancient pyramids and ceremonial sites.

The Middle Ages

In Western societies, red was associated with martyrdom and sacrifice, due to its obvious link to blood. Starting in the Middle Ages, Catholic popes and cardinals wore red to honor the blood of Christ and early Christian martyrs.

During the First Crusade, soldiers marched under banners of a red cross on a white field—the Cross of Saint George, which later became the national flag of England and remains part of the United Kingdom’s flag today.

By 1295, cardinals wore red robes. Abbot Suger’s renovation of the Basilica of Saint-Denis introduced stained glass in vibrant red and blue, influencing the use of color in cathedrals throughout France, England, and Germany. In medieval painting, red often adorned Christ and the Virgin Mary to draw visual focus.

Charlemagne painted his palace red and wore red shoes to symbolize his imperial authority.

The Renaissance

During the Renaissance, red gained prominence as a color of divine focus. Venetian master Titian mastered red’s power, using layered vermilion glazes to create luminous garments for Christ, the Virgin Mary, and apostles.

Queen Elizabeth I favored bold reds in her wardrobe before adopting her austere “Virgin Queen” image.

In Renaissance Flanders, red was worn by all social classes during festivities. Dutch master Johannes Vermeer skillfully layered vermilion and madder glaze to create the radiant red skirt in The Girl with a Wine Glass.

18th to 20th Century

At the end of the 18th century, during a dockworkers’ strike in England, laborers began waving red flags. This symbol soon became tightly associated with the emerging workers’ movement, and later with the British Labour Party, officially founded in 1900.

In Paris, in 1832, a red flag was carried by workers’ protestors during the failed June Rebellion—a moment immortalized in Victor Hugo’s Les Misérables. The red flag appeared again during the 1848 French Revolution. At that time, it was proposed as the new national flag of France, symbolizing revolutionary unity and struggle. However, the poet and statesman Alphonse de Lamartine strongly opposed its adoption, instead upholding the blue-white-red tricolor as the emblem of the Republic.

Nonetheless, the red flag returned in 1871 as the banner of the short-lived Paris Commune, a radical socialist government that governed the capital for just two months but forever shaped the visual language of rebellion. Afterward, the red flag was adopted by Karl Marx and numerous European socialist and communist movements, becoming the international symbol of proletarian revolution.

Reproduction of Red

Red sits at the far end of the visible light spectrum, just after orange and before the violet range. Its dominant wavelength falls between 625 and 750 nanometers.

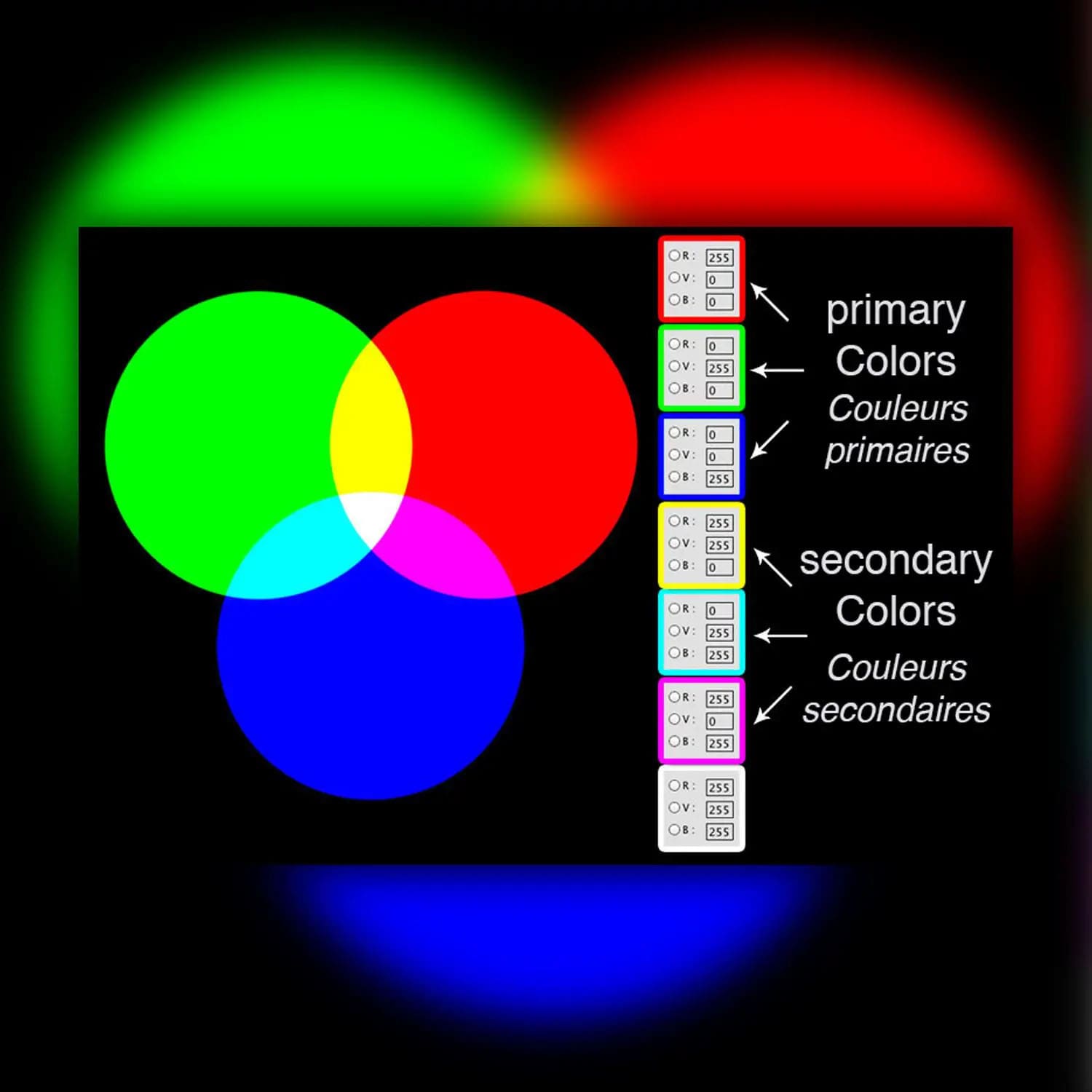

In the RGB color model (used in screens and digital display), red is a primary additive color. In the CMYK color model (used in printing), red is considered a secondary subtractive color, created by mixing magenta and yellow.

Red is also the complementary color of cyan. Its hues span from scarlet and vermilion (closer to orange) to crimson and burgundy (closer to blue). Its tones vary from light pinks to deep oxbloods.

In CMYK models, red is created by subtractive mixing, combining magenta and yellow inks or pigments. In contrast, the RGB model creates red through additive mixing of light. Red, green, and blue are the additive primaries—when combined at full intensity, they produce white light. This principle powers digital screens, televisions, and LED displays.

For example, magenta on a computer screen is produced by combining equal intensities of red and blue light—a digital mirror to Renaissance artist Cennino Cennini’s pigment methods, but rendered through light and code instead of oils and glazes.

Violet, too, is produced on digital screens through additive color mixing: a greater intensity of blue light, mixed with less red, displayed over a black background.

This section of the spectrum is where art, physics, and digital technology intersect—making red not just a symbolic or emotional force, but a scientific one, shaping how we perceive and build the visual world.

The Symbolism of Red

The Heart

The heart symbol is used to express the idea of “heart” in its symbolic sense—most often representing the center of human emotion, especially affection and love, and above all, romantic love. Though its origins trace back to antiquity, the familiar heart shape as we know it today became widely established in Europe during the Middle Ages.

Over time, it developed several emotional variations. Sometimes it was replaced or accompanied by the motif of the “wounded heart”, typically shown pierced by an arrow—signifying heartbreak or unrequited love. In other depictions, a “broken heart” appears split into two or more pieces, symbolizing the anguish of separation or emotional loss.

Since the 19th century, the heart symbol has been reproduced endlessly across the objects and imagery of popular culture, becoming the go-to icon for expressing romantic feelings. It became inseparable from another enduring emblem of love: the red rose. We give red roses on meaningful occasions precisely because of their fragrance, beauty, and cultural weight. From antiquity to the modern era, poets, writers, and painters have extolled the red rose as the very embodiment of passion, femininity, and sensuality.

The heart also evolved linguistically—used as a logogram in place of the word “love.” This practice gained international fame with the now-iconic phrase “I ♥ NY”, first introduced in 1977, which forever tied the graphic heart to the English verb “to love.”

In heraldry, hearts gained symbolic strength as well. In the modern era, heart-shaped charges appeared frequently in ecclesiastical heraldry through representations of the Sacred Heart, while more secular uses of the heart as a symbol of love emerged in the bourgeois coats of arms.

Later, the motif extended into municipal heraldry, where the heart became a popular decorative and symbolic element in city emblems, showing how this symbol—once private and intimate—evolved into a marker of collective identity and shared emotion.

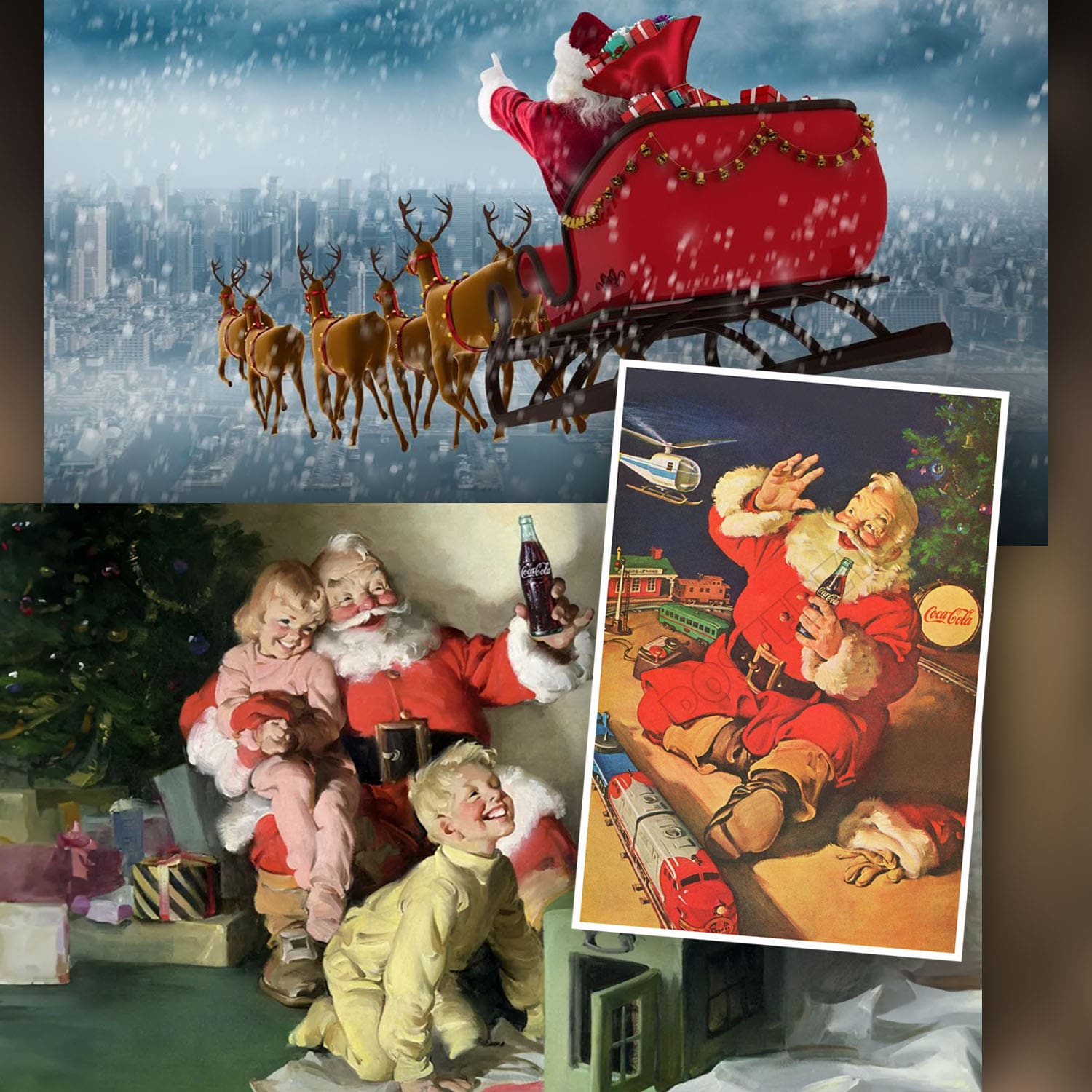

Santa Claus

Santa Claus is a legendary figure originating in Western Christian culture, said to bring gifts to children late at night and into the early hours of Christmas Eve. According to tradition, Santa’s elves craft the gifts in his North Pole workshop, while a team of flying reindeer pulls his sleigh through the skies to deliver them.

The popular conception of Santa Claus draws from the folklore surrounding Saint Nicholas, a 4th-century Christian bishop and the patron saint of children. Saint Nicholas became famous for his generosity and acts of secret giving. His persona merged over time with various regional traditions, particularly the English figure of Father Christmas, and they are now broadly considered to be one and the same.

Today, Santa Claus is almost universally depicted as a jovial, heavyset man with a white beard, sometimes wearing glasses, and dressed in a red coat trimmed with white fur, red trousers with fur cuffs, a red hat bordered in fur, and black leather boots and belt. He’s almost always shown carrying a large sack of gifts slung over his shoulder. His signature laugh—“ho, ho, ho!”—is a hallmark of Christmas imagery, used in literature, songs, films, and advertising alike.

This now-iconic image emerged in the United States in the 19th century, after Dutch settlers introduced the legend of Sinterklaas (Dutch for Saint Nicholas) to New Amsterdam—present-day New York City—in the 17th century.

The transformation was solidified by the 1823 poem A Visit from St. Nicholas (commonly known as ’Twas the Night Before Christmas), which described Saint Nicholas arriving in a miniature sleigh pulled by eight flying reindeer. This poem laid the foundation for modern depictions of Santa Claus and embedded him as the spiritual and festive centerpiece of Christmas in American culture.

Over time, this image of Santa was reinforced through music, radio, television, children’s books, family traditions, films, and especially advertising.

One of the most enduring and widespread visual interpretations of Santa Claus came from Haddon Sundblom, an illustrator who created a series of Christmas ads for The Coca-Cola Company in the 1930s. His illustrations presented Santa as the red-suited, warm-faced, beaming figure we recognize today.

These Coca-Cola campaigns sparked persistent urban legends, claiming that Santa Claus was “invented” by the brand, or that he wears red and white because those are Coca-Cola’s signature colors. While the campaigns were undeniably influential in shaping Santa’s global image, they did not invent it.

Other beverage companies—such as Pepsi-Cola—also used similar imagery in their advertising during the 1940s and 1950s.

In fact, Santa Claus had already appeared in red-and-white attire on various covers of Puck Magazine in the early 1900s. Even earlier, White Rock Beverages used a Santa figure in black-and-white advertisements for mineral water in 1915, and in color ads for their drink mixers between 1923 and 1925.

Thus, the image of Santa Claus as we know it—a red-suited, white-bearded, gift-bearing patriarch of joy—was not a singular corporate invention but the result of a long cultural evolution, rooted in Christian generosity, reshaped by American imagination, and broadcast globally through commerce and media.

Communication & the Color Red

Warning and Danger

Red has long been associated with alertness and peril. In medieval warfare, a red flag meant “no prisoners.” Pirates flew red to signal no mercy.

In modern sports, a red card means ejection. In auto racing, a red flag signals extreme danger.

Red is the international color for stop signs, traffic lights, and hazard signs, formalized by the Vienna Convention on Road Signs in 1968. It was chosen not just for its psychological weight, but for its contrast against natural backdrops like sky, foliage, or asphalt.

Studies show red evokes the strongest physiological reaction among all colors—more than orange, yellow, or white.

Red as the Center of Attention

Red draws the eye. People wearing red appear closer than they are. The color is linked with energy, action, visibility, and extraversion.

Major brands such as Coca-Cola, Target, Ray-Ban, and Levi’s use red in their logos to convey passion, trust, and power. It’s no accident red remains a branding cornerstone.

Seduction & the Color Red

Red is, by far, the color most commonly associated with seduction, sexuality, eroticism, and moral transgression—a reputation it owes to its deep connection with passion and danger.

For centuries, red has carried with it an undeniable aura of temptation. In Christian theology, it was long seen as a color with a dark undertone, symbolizing sexual passion, anger, sin, and even the Devil himself.

In the Old Testament, the Book of Isaiah reads:

“Though your sins be as scarlet, they shall be white as snow.”

This association between sin and crimson firmly tied red to moral and emotional extremes.

In the New Testament, the Book of Revelation presents the Antichrist as a red beast, ridden by a woman “clothed in scarlet”—a figure known as the Whore of Babylon. But rather than dwell solely in religious judgment, this image reveals how red evolved into a visual shorthand for female sexual power, both feared and worshipped.

Over time, Satan himself came to be represented in red—whether in crimson robes or horned costumes—both in Christian iconography and later in popular culture. By the 20th century, the “devil in red” had become a recurring character in legends, fairy tales, cartoons, and films—more symbolic mischief than religious menace.

In 17th-century New England, red took on another infamous role: it became the color of adultery. In Nathaniel Hawthorne’s 1850 novel, The Scarlet Letter, a Puritan woman is punished and shunned for committing adultery, forced to wear a large red letter “A” sewn onto her clothing—a mark of shame and moral branding. The title alone made red an enduring symbol of forbidden desire and female transgression.

Red’s association with prostitution is equally longstanding. Across different eras, sex workers were often required to wear red garments to clearly signal their profession in public. Brothels displayed red lanterns outside their doors to indicate their purpose—a tradition that gave rise to the modern term “red-light district.”

From the early 20th century onward, prostitution became restricted to designated zones, known euphemistically as “hot neighborhoods” or quartiers chauds, further cementing red’s identity as the color of sensual commerce and illicit allure.

In both Christian and Hebrew traditions, red is also tied to bloodshed and guilt—captured in expressions like “caught red-handed” or “with blood on one’s hands.”

But despite all these historical burdens, red remains a paradoxical symbol: it is the color of desire and scandal, but also of celebration and confidence. It intoxicates, disrupts, seduces.

To wear red is to enter a conversation with history—flirt with the edges of what society deems acceptable—and assert power through visibility, intention, and presence.

Fashion & the Color Red

Red entered the world of fashion with defiance, elegance, and sensuality. It was not a color to be worn lightly—bold, charged, and unforgiving, red required mastery. It demanded to be wielded with precision by designers who understood its emotional power and symbolic gravity.

Houses like Christian Dior, Yves Saint Laurent, Fendi, and Dolce & Gabbana—each in their own way—have explored red’s many dimensions, pairing it with black for drama, with white for purity, with gold for power, or allowing it to stand alone as the uncontested protagonist of a collection.

Yet historically, red carried a social weight that wasn’t always glamorous.

In the 19th century, red was deemed vulgar, tied to the image of courtesans and prostitutes. A bourgeois woman would avoid it at all costs. Instead, she powdered her face with rice flour, aiming for a pale, chaste complexion. Rouge on the lips or cheeks was scandalous—belonging to women of “ill repute.” In many cities, sex workers were required by law to wear a red article of clothing in public, to identify themselves unambiguously. At the entrance of brothels, a red lantern signaled what lay beyond the threshold.

But fashion has a way of reclaiming the forbidden.

Today, to wear red is to project confidence, control, and self-awareness. It can be wildly sensual, strikingly regal, or achingly romantic. But it is never passive. Red makes a statement before the wearer even speaks.

“Wearing red is audacious. It can be elegant—but only if you feel the color.

If you master it, red will make you beautiful. If you don’t, it will destroy you.”

— Guillaumette Duplaix

Among the houses that have mastered red, one name stands above all others: Valentino.

Valentino

Valentino Garavani didn’t just use red. He elevated it to a sacred code within his fashion house. So deeply intertwined with the designer’s identity, the shade became known worldwide as “Valentino Red.”

So iconic is this color that it has its own Pantone formula:

100% magenta, 100% yellow, 10% black—a mix that results in a radiant, saturated red with hints of warmth and nobility.

Valentino first introduced red in his debut collection in 1959. The moment was not just aesthetic—it was deeply emotional. According to legend, Valentino had an epiphany at the Barcelona Opera, watching women dressed in red on stage.

“They looked like a bouquet of geraniums,”

he recalled. “From that moment, I knew: red was going to be my signature.”

But Valentino’s red was never simply visual—it was philosophical.

“Red is a color I have carried with me since childhood,”

Valentino said. “It has such vitality and such charm, I love to see it not only in clothing, but in homes, flowers, objects, and details.

It’s my good luck charm. A woman in red is always flawless: it’s flattering, it suits everyone.

It’s a strong color, and yet a non-color. Like black, brown, blue, or white. It’s not a pale green, or a pastel.

Red gives energy. Red gives refinement.

Red is life. Red is passion. Red is love.”

Under Pierpaolo Piccioli, the Valentino house has redefined its red legacy for the 21st century. Most notably, in the Fall/Winter 2022 Haute Couture collection, Piccioli unveiled a monochromatic series in hot pink, dubbed “Valentino Pink PP”—a direct conceptual descendant of Valentino Red. In doing so, he honored the tradition by reinventing its expression.

But make no mistake—Valentino Red remains the eternal muse, reappearing season after season, collection after collection.

From red gowns sweeping the Met Gala staircase to bridal couture in crimson silks, Valentino has turned red into a fashion language of its own—a language of sensuality, sovereignty, and strength.

Red Across the Runway

Other designers have wielded red to communicate narrative and power.

- Alexander McQueen infused red with violence and beauty—combining it with black leather, roses, and razor-sharp silhouettes.

- Dolce & Gabbana embrace red as an ode to Sicilian baroque—bold, religious, and deeply Mediterranean.

- Yves Saint Laurent, in his smoking jackets and couture gowns, balanced red with restraint—proving that it could be both sultry and sophisticated.

Today, red remains one of the most enduring and emotionally loaded colors in fashion. It appears in every collection with a different voice—sometimes a whisper, sometimes a scream. But always with purpose.

Conclusion

Across continents and centuries, red has never been neutral.

It’s not a background color. It’s not decoration.

Red is a force. A signal, a seduction, a scar, a crown.

From the cave walls of prehistory to the velvet capes of popes, from the blood-soaked flags of revolution to the lacquered runways of Paris, red has marked humanity’s deepest instincts—love, war, power, sex, sacrifice, divinity.

It is the color of the heart that beats and the wound that bleeds. The color of the kiss and the curse.

In fashion, red doesn’t follow trends. It stands outside them.

It is, quite literally, the color of consequence.

“The true color of life is the color of the body,

the color of the covered red,

the implicit and not explicit red of the living heart and the pulses.

It is the modest color of the unpublished blood.”

— Alice Meynell, poet and essayist (1847–1922)

Red refuses to whisper. It speaks in emotion, not logic. In temperature, not tone.

And while other colors may flatter the surface, red tells the truth about what’s underneath.

It wraps itself around those who dare:

The romantics. The rebels. The visionaries. The queens.

The shy may reach for just a touch of it—a crimson lip, a scarlet heel.

The bold will drape themselves in it from throat to toe.

And both will feel its power: the way it emboldens, seduces, protects, and ignites.

Because red is not a color.

It is a mood, a message, a movement, and sometimes, a mirror.

It asks:

Are you ready to be seen?

Or are you still hiding behind pastels?

Red will not wait for you to feel ready.

It already knows who you are.

Guillaumette Duplaix

Editor, Cultural Historian, and Keeper of Colorful Truths